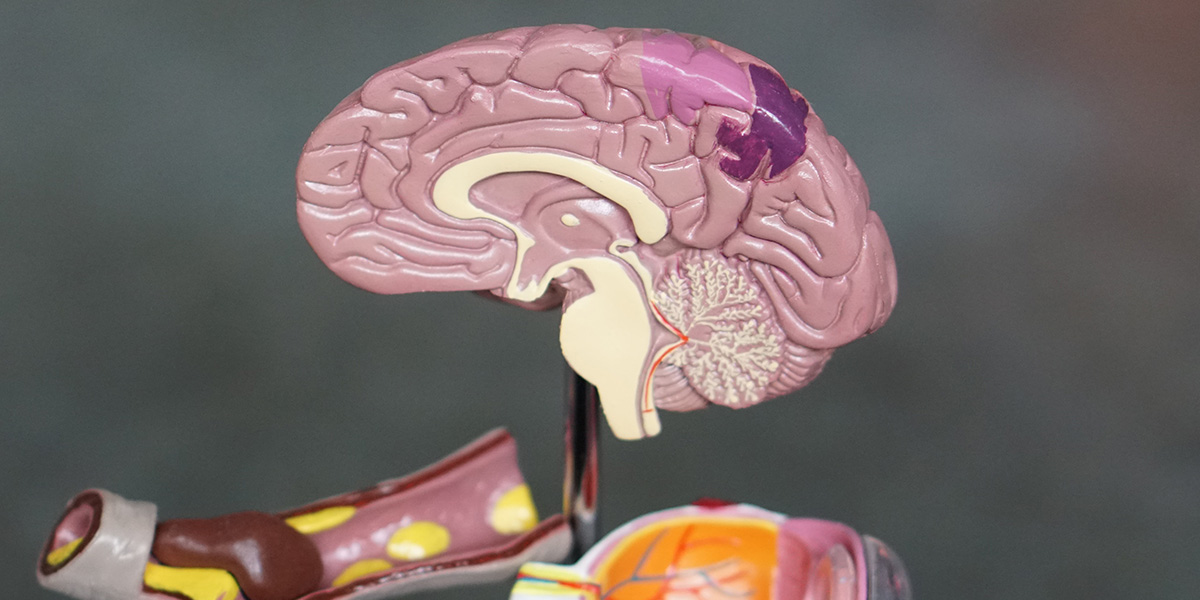

According to the World Health Organization, Dementia is a syndrome of a chronic or progressive nature in which there is a deterioration in cognitive function (i.e. the ability to process thought) beyond what might be expected from normal aging. It affects memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, calculation, learning capacity, language, and judgment, but consciousness is not affected. The impairment in cognitive function is commonly accompanied and occasionally preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, social behavior, or motivation.

Dementia is most prevalent among people aged 60 and over. Statistics indicate that the median age of Canadians is rising and people are living longer. Consequently, the number of Canadians who suffer from dementia is also increasing.

Dementia does not of course just affect Canadians. Worldwide, there are nearly 10 million new cases of dementia reported every year. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia and contributes to approximately 60 to 70% of cases. There are a number of other forms including vascular and Lewy Body dementia.

According to the Alzheimer Society, 937,000 Canadians will be living with Alzheimer’s disease in 15 years. 1.1 million Canadians are directly or indirectly affected by the disease which now costs Canadians an annual cost of $10.4 billion.

Dementia can render a person incapable of making legal/financial and/or healthcare decisions.

If that person planned for their eventual incapacity by executing an enduring power of attorney or representation agreement while they were still capable of doing so, then the attorney or representative under either of those instruments would be able to step in to assist in many (but not necessarily all) cases. However, if no such incapacity planning instruments were made in advance, the incapable person may need to have a committee appointed by the court to make decisions on their behalf. (It is worth recalling that in addition to powers of attorney and representation agreements, another incapacity planning tool is a ‘nomination of committee’ whereby a person designates who they want to be their committee in the event such a step is necessary.)

In British Columbia, the Patients Property Act provides the legal basis for appointing a committee for a person found incapable of managing their personal care or financial affairs.

Before a committee can be appointed, the court must be satisfied that the medical evidence demonstrates that the person is incapable.

Specifically, the Act requires affidavits from two medical practitioners setting out their opinions that the person who is the subject of the application is incapable of managing herself or her affairs because of mental infirmity arising from disease, age or otherwise. The Act permits the court to order the person who is the subject of the application to attend and submit to a medical examination. However, if the subject of an application refuses to attend a medical assessment, the court cannot order a medical examination unless there is a sufficient evidentiary basis for the order.

Court Ordered Medical Examinations

In some cases, the person who is the subject of a committeeship application may resist being declared incapable and refuse to submit to a medical examination by a doctor who has been asked to provide their opinion to be set out in an affidavit. Such an examination may be necessary in cases where the person had only seen their family doctor recently and no other doctor could provide the necessary second affidavit without the benefit of seeing and assessing the person.

In the British Columbia Court of Appeal decision in Temoin v. Martin, the Court held that it had the authority to order the person to attend a medical assessment under its ‘parens patraie’ jurisdiction powers, but it would only do so where there were both strong indications that the person was incapable and was in need of protection. (The ‘parens patraie’ jurisdiction is a power to assist vulnerable persons who are not able to assist themselves.)

The Court in Temoin held that the applicant for an order for a medical assessment, who was the daughter of the person who was alleged to be incapable, had failed to convince the Court on either of those two points and therefore the request failed. The Court noted that each case turned on its own facts and the applicant’s case, unfortunately for her, was focused on the applicant’s concern about a will made by her father that favored his second wife’s family over the daughter.

The result in Temoin effectively precluded the daughter from having her father declared incapable and having herself appointed his committee because she was not able to place before the Court the two medical affidavits attesting to the father’s incapacity that the Act requires.

Different Legal Tests for Capacity for Different Contexts

It is important to recognize that a diagnosis of dementia does not necessarily mean that a person is incapable of managing their affairs. Dementia is generally a progressive illness and persons with an earlier stage of the condition may still be found to be capable.

In addition, the law has developed different standards for incapacity for different legal contexts. As noted by the Court in Temoin, the incapacity test under the Act is different than the test for the mental capacity necessary to make a valid will (testamentary capacity). It is also different from the tests for the capacity to appoint an attorney or a representative or nominate a committee. Therefore it is possible that a person found to be incapable under the Act may be found to have the capacity to make a will.

Discuss Your Situation with an Experienced BC Committeeship Lawyer

If you believe that a family member can no longer make decisions to properly manage their personal, legal or financial affairs and therefore require a committee appointed, McLarty Wolf has extensive experience and expertise in handling committeeship cases. Contact us at 604-687-2277 or fill out our online contact form for assistance.

You must be logged in to post a comment.